A couple of years ago, I said to Reg that I hoped the monument could be located within sight of the statue to Thomas Ruffin, author of the infamous State v. Mann, which handed to masters almost unlimited power to suborn their slaves through physical "correction." At that time, it was not clear where the monument would be sited.

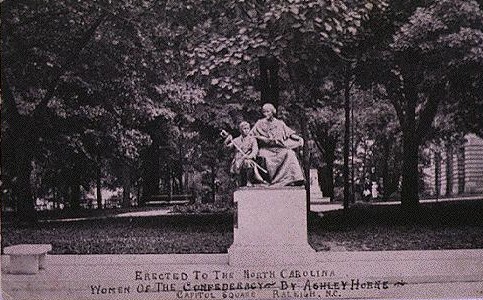

Symbolically, there could be no better location than Union Square, home of so many of what Catherine Bishir has called the state's "landmarks of power" that by 1915, when the Ruffin statue was erected, some had already said the square was too crowded. Ruffin ended up in an alcove at the entrance to what was then the Supreme Court building, now the Court of Appeals; the spot considered ideal, on Union Square across from the court building, had just been taken by the 1914 monument to the Women of the Confederacy.

Some other monuments on the square include the 1892 Confederate Monument, unveiled by Stonewall Jackson's granddaughter precisely 34 years after North Carolina seceded from the Union; a statue of Henry Lawson Wyatt, the first Confederate soldier to die in battle; and elaborate monuments to Charles Aycock, the "education governor" more recently known for his participation in the Wilmington coup of 1898, and Zebulon Vance, North Carolina's governor during the Civil War and again after the war as federal troops left the state. These monuments were all erected during the great period of the solidification of conservative Democratic power and the institutionalization of Jim Crow. As Bishir writes,

As the southern elite took control of the political process during the decades spanning the turn of the century, it also codified a view of history that fortified its position in the present and its vision of the future.

Throughout America in the decades just before and after 1900, political and cultural elites drew on the imagery of past golden ages to shape public memory in ways that supported their authority. By commissioning monumental sculpture that depicted American heroes and virtues in classical terms, and by reviving architectural themes from Colonial American, classical Roman, and Renaissance sources, cultural leaders affirmed the virtues of stability, harmony, and patriotism. The principal shapers of public memory and patrons of public sculpture and architecture in Raleigh and Wilmington, centers of political and cultural activity in the state, were members of an established elite. They were akin to aristocrats throughout the nation and they were well acquainted with national cultural trends. They also shared certain backgrounds, experiences, and values. All were Democrats, and, with a few notable exceptions, they were members of families of long-established social and economic prominence.

The Freedom Monument Project's supporters have pointed out that "except for an anonymous, wounded black soldier in the N.C. Vietnam Veterans Memorial, blacks are not represented on the State Capitol grounds." This monument proposes to correct that oversight. It holds the promise of inspiring whole new interpretations of the existing landmarks on and around Union Square--including the imposing statue of Judge Ruffin.

After a bill introduced into the Legislature in 1911 by Gen. Julian Carr of Durham County to appropriate funds for a memorial to the women of the Confederacy failed to pass, Col. Ashley Horne put $10,000 of his own money toward the design and construction of the monument.

Thomas Ruffin's steady gaze still meets visitors to the North Carolina Court of Appeals. The statue was funded by the North Carolina Bar Association and Ruffin's family.

No comments:

Post a Comment