Tuesday, November 30, 2004

Flippin' out

(Via kottke.)

On the internet, possibly somebody does know you're a dog.

Monday, November 29, 2004

Tomorrow came and went.

Saturday, November 27, 2004

Remembering the last bus out

UPDATE: Mystery unveiled! Brian Russell has a fascinating interview with Matt Robinson, one of the creators of this work called "Seven Windows, Seven Doors." He talks about motivations and meanings in the post-election climate in which the work was generated. Thanks, Ruby.

By the way, I wish my photos were better, but they were taken through a chain link fence with an unsteady zoom.

More examples of "stencil graffiti."

Thursday, November 25, 2004

Mixed blessings

What Thanksgiving is is a hodgepodge, a cornucopia of ritual and myth. Texans near El Paso claim that their ancestors beat the Pilgrims by many years with a celebratory feast of fish, "many cranes, ducks and geese." The "first Thanksgiving" story and other claims about the Pilgrims (and what they ate) are debunked regularly by serious historians.

Charles E. Mann writes that it was a 1914 painting, "The First Thanksgiving," by Jennie Augusta Brownscombe, that fixed in childhood our images of the historical event. Not only is the presence of turkey on the table wrong, he suggests: the painting masks the real picture of what European colonization was already doing to the North American ecology.

Until the arrival of the Mayflower, continental drift had kept apart North America and Europe for hundreds of millions of years. Plymouth Colony (and its less successful predecessor in Jamestown) reunited the continents. Ecosystems that had evolved separately for millennia collided. The ensuing biological tumult--plants exploding over the landscape, animal species spiking in population or going extinct--had consequences as profound as those from the cultural encounter at the center of Brownscombe's painting.Today in these parts it is English ivy, microstegium, kudzu, multiflora rose.

In a phenomenon known as "ecological release," imported species can run wild because their natural predators have not come along with them. Clover and bluegrass, tame as accountants at home, transformed themselves into biological Attilas in the Americas, sweeping through vast areas so fast that the first English colonists who pushed into Kentucky found both species waiting for them. The peach proliferated in the Southeast with such fervor that by the 18th century, the historian Alfred Crosby writes, farmers feared that the Carolinas would become a wilderness of peach trees.

South America was just as badly hit. Endive and spinach escaped from colonial gardens and grew into impassable, six-foot thickets on the Peruvian coast; thousands of feet higher, mint overwhelmed Andean valleys. In the pampas of Argentina and Uruguay, the voyaging Charles Darwin discovered hundreds of square miles strangled by feral artichoke. "Over the undulating plains, where these great beds occur, nothing else can live," he observed.

Intercontinental cross-fertilization of law students and other human types is a wonderful thing. But it's no secret that our European ancestors badly mismanaged their new environment. For one thing, they failed to use the Indians' primary land-management technique: controlled burning. "When disease carried away native societies," Mann observes,

the torches went out. Trees and underbrush erupted in ways that had not been seen for millennia, filling in areas kept open by Indian axes and Indian fire. "Almost wherever the European went, forests followed," wrote the ecological historian Stephen Pyne. Far from destroying wilderness, in other words, European settlers created it--only it was a peculiar, unprecedented kind of wilderness, shot through with European invaders and characterized by population outbreaks from species that had formerly been uncommon.

"What was being created that first Thanksgiving," he concludes, "was nothing less than the American landscape itself."

Wednesday, November 24, 2004

Media alert

UPDATE: The lowdown.

Tuesday, November 23, 2004

The dream of a common language

Alas, it was a grand idea, one that I mostly forgot about, for the reason that it is mostly forgotten.

If you look around today, you'll still read, as I'm sure I did, that Esperanto was "introduced in 1887 by Dr. L.L. Zamenhof after years of development." But I didn't know till I read in Aaron Lansky's fascinating book Outwitting History: The Amazing Adventures of a Man Who Rescued a Million Yiddish Books that Dr. Zamenhof was a Jew--a Russian Jew.

Esperanto has been recently taught at Rice University by Neal Parker, who has a nice history of the man and the language.

In Warsaw as a teenager, Zamenhof applied his prodigious capacity for languages (and the emerging field of linguistics) toward solving the contentious problem of communication across ethnic lines.

In Tsarist Russia, his father had good reason to worry about stray papers lying about in a foreign language. The father, though recognizing his talent, discouraged and dissauded. The son promised to go to Moscow and study medicine (that being one of the few professions open to Jews in Russia), in exchange for his father's promise not to destroy his work. The son kept his promise, but the father did not.

The son became a doctor, but he "found it difficult to cope with the suffering of his patients." He turned to ophthamology.

The father of the woman he married financed the publication of his renewed linguistic work.

Zamenhof decided to publish in Russian partly because books in Russian were viewed with less suspicion by the government censors, and he decided to use a pseudonym lest suspicions of eccentricity cause damage to his professional career. . . . He intended for his language to be called lingva internacia but the pseudonym that he chose, Dr. Esperanto, soon came to designate the language as well as the author.

Esperanto means (in Esperanto) "one who is hoping."

Despite a crisis or two, Esperanto lives on. As one might imagine, it doesn't do so well during times of war. "World War I was very damaging to the movement. After slaughter on such a large scale it was difficult to recreate the spirit of hope and optimism that had flourished before the war."

The French are steadfast supporters of Esperanto.

The 90th annual Congress on Esperanto will take place next year in Vilnius. Czeslaw Milosz, who was once fired from a Vilnius radio station for his leftist politics, might have been amused.

What the cameraman saw

I interviewed your Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Willy Buhl, before the battle for Falluja began. He said something very powerful at the time-something that now seems prophetic. It was this:

"We're the good guys. We are Americans. We are fighting a gentleman's war here--because we don't behead people, we don't come down to the same level of the people we're combating. That's a very difficult thing for a young 18-year-old Marine who's been trained to locate, close with and destroy the enemy with fire and close combat. That's a very difficult thing for a 42-year-old lieutenant colonel with 23 years experience in the service who was trained to do the same thing once upon a time, and who now has a thousand-plus men to lead, guide, coach, mentor--and ensure we remain the good guys and keep the moral high ground."

I listened carefully when he said those words. I believed them.

So here, ultimately, is how it all plays out: when the Iraqi man in the mosque posed a threat, he was your enemy; when he was subdued he was your responsibility; when he was killed in front of my eyes and my camera--the story of his death became my responsibility.

The burdens of war, as you so well know, are unforgiving for all of us.

I pray for your soon and safe return.

Images against war

Monday, November 22, 2004

Blah blah blog

Sunday, November 21, 2004

Thursday, November 18, 2004

Proportional representation

Tuesday, November 16, 2004

What tripe

Sunday, November 14, 2004

Lost and found

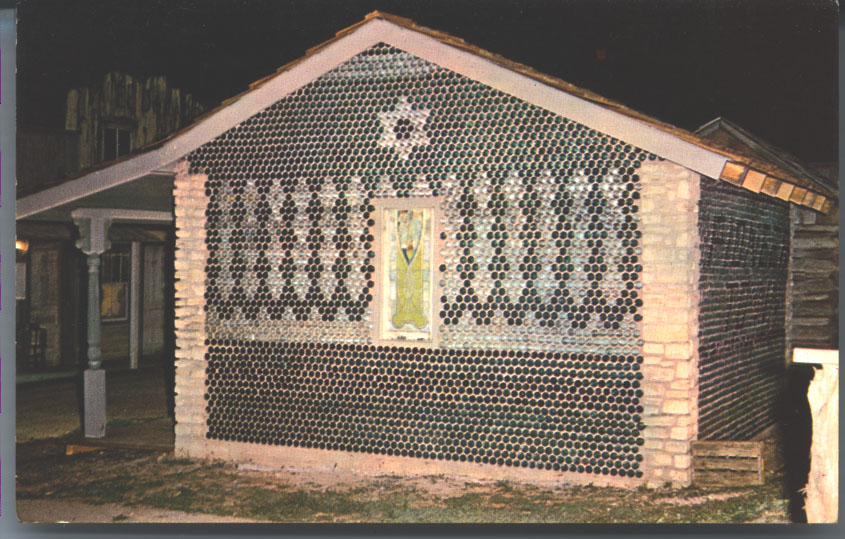

The Bottle House, Pioneertown, Wimberley, Texas

"Built of over 9500 sodawater bottles and lighted from the inside, it glows brilliantly at night."

"Small miracles" department: Half of my long-lost postcard collection has been found, and a hopeful search continues. About this and other losses I once wrote,*

For reasons large and small, I've been thinking about losing things--about how much loss a person has to bear up against in the course of just one ordinary lifetime.

Like my postcard collection: two bulging file draws of them, a pictorial diary, glossy and idealized, of a well-traveled childhood. It was organized geographically. Texas loomed largest, of course: the San Antonio river walk, the Fort Worth Zoo, the Humble Building on the Houston skyline, a house made of bottles at a Wimberley dude ranch, the HemisFair.

And in other categories, the 1964 World's Fair, the White House, Niagara Falls. Novelty postcards, such as a copper-coated one from Utah to which was attached a tiny bag of salt from the Great Salt Lake. Antique cards bought in Jefferson, bearing traces of the lives, and losses, of strangers.

Cards sent to me from places I thought I might never see, some of which I still may not: London, Paris, Jerusalem, Constantinople (to call it by its lovelier name).

There was even a postcard with my picture on it. Barely recognizable, Nancy Harrison and I sat on the pier in a long shot of the lake at Camp Nottawa. We were in Camp Fire uniforms. Were bathing suits unsuitable on fourth grade girls? This was one of a handful of local cards that for a while could be bought at the Dairy Queen, though I noticed that they never seemed to disappear.

All are lost now.

A poem by Elizabeth Bishop, which I have memorized so as not to lose, is some consolation.

The art of losing isn't hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

. . .

[More]

1968 World's Fair HemisFair, San Antonio

Institute of Texan Cultures

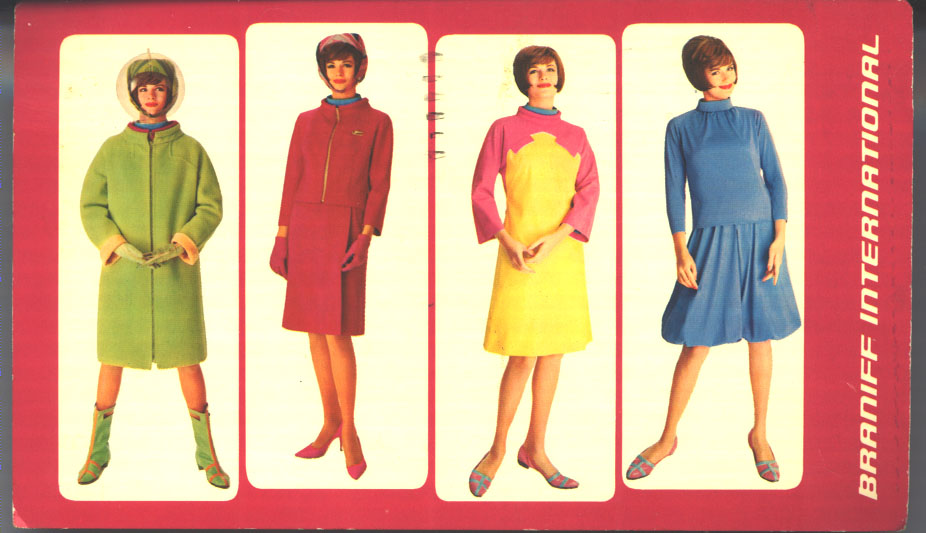

The End of the Plain Plane

"You can fly with our airline seven times and never fly the same color airplane twice."

High Fashion Quick Change

"Braniff International airline hostesses are outfitted in a couture collection by Emilio Pucci. They can make four changes in a single flight."

Seeing Niagara Falls from "Maid of the Mist"

"The voyagers are swathed in oilskins as a defense from the saturating spray and the spectacle of the mighty volume of water, passing over the precipice 160 feet above, to fall in thunder on the rocks below, is as magnificent as it is impressive."

Statue of Liberty at Night

"Standing on Bedloe's Island, 1 3/4 miles from the Battery, it symbolizes 'Liberty Enlightening the World.'"

Recruiting poster, 1917, James Montgomery Flagg

*"Views from Carolina," The Gilmer Mirror, July 1998.

Saturday, November 13, 2004

The first thing we do . . .

This week, federal district judge James Robertson ruled that a Guantanamo prisoner could not be tried by military commission until "a competent tribunal determines that [he] is not entitled to protections afforded prisoners of war under Article 4 of the Geneva Convention ... of Aug. 12, 1949." And the President--who has declared all Guantanamo detainees "enemy combatants" exempt from the Geneva Conventions--"is not a 'tribunal,'" Judge Robertson wrote.

For every action, there is a swift and opposite reaction. At a gleeful meeting of the Federalist Society on Thursday and Friday, John Ashcroft minced no words:

Mr. Ashcroft had many in the crowd rapturous when he criticized judges who, he said, refused to recognize that they did not have the power to limit the president's authority to conduct a war against terrorists.

"The danger I see here," he said, "is that intrusive judicial oversight and second-guessing of presidential determinations in these critical areas can put at risk the very security of our nation in a time of war."

The hostility to judicial review that Ashcroft shares with the Bush Administration was echoed even more plainly at this meeting by Justice Scalia:

"It is blindingly clear,'' he said, "that judges have no greater aptitude than the average person to determine moral issues."The first thing to be done by the new Bush Administration is to take care of all the judges. Lawyers with dissenting readings of the Constitution are put on notice.

*I'm using this tired old line in a lawyerly way, but I can't help it.

UPDATE: Eric Muller is on the case, and Jack Balkin has some advice.

Thursday, November 11, 2004

Veterans Day thought: "Vietnam"

The men who rose up in anger after Marrow's killing may have felt that the streets of Oxford were their Vietnam, but their message went beyond that. These were men who had fought in Vietnam. In swamps and jungles thousands of miles from home, they risked death to defend American democracy. Like the black veterans of two world wars before them, they might well have wondered what they got from it all in return. To inscribe "Vietnam" on the grave of a black victim of racial hatred in rural North Carolina in 1970 is to draw a profound connection.

Wednesday, November 10, 2004

What you didn't hear on WUNC this morning

Fundraising is important, as Paul noted, but the sad thing about this is that WUNC is the station they listen to in Oxford. The station's response this morning was an apology combined with the suggestion that people could hear it on the internet. I don't know, but I suspect that that won't exactly do it up in Oxford.

They did get the benefit of Tyson's company at their annual "Diversity Banquet" this year, however, which was surely a memorable occasion.

Tyson, who described some of the segregation conditions in Oxford in his book and in his talk, said some are asking, "Why dredge all this up now?"You can hear the interview here. I recommend it.

He gave a historian's answer:

History is not just the past, he said, but the present and the future, and knowing the past is necessary to understand the present. "It matters how we explain ourselves to ourselves."

UPDATE 11/11: They ran it this morning, we were happy to hear. After they said they couldn't because it had come over the live satellite feed and they couldn't get it back, this represents a victory of the call-in campaign that Tim organized. Good work!

Tuesday, November 09, 2004

Street should be named for local hero

Picture it 1959. "Gradualism" will longer appease, but shall it be resisted with violence or coercive nonviolence? "When we look back at history," writes Tim Tyson in his book on North Carolina civil rights activist Robert Williams,

it is important to resist the temptation to view all events as part of an inexorable chain of causality leading inevitably to the present. Nonviolent direct action was a fortunate but certainly not an inevitable course or strategy. Nor did it have deep roots in Southern black culture. Though nonviolence was compatible with the distinctive Afro-Christianity of the black South, it was not interchangeable with it. To understand its full-blown emergence with the sit-in movement in the spring of 1960, we must understand what nonviolence was and what it was not. We must understand, too, that for most black Southerners nonviolence was a tactical opportunity rather than a philosophical imperative. Thus we must reconsider that time before the sit-ins swept the South, before the founding of SNCC, before the Freedom Riders rolled through Dixie, before Albany and Birmingham and Selma etched their mark on human history, and before the dream of Martin Luther King Jr. captured the moral imagination of the world, when the course of events still might have gone quite differently.

On February 1, 1960, four black students from North Carolina A&T decided to have a seat at a Greensboro lunch counter. Their action seemed to settle the question. "[T]he sudden emergence of the student movement after the Greensboro sit-ins . . . temporarily set aside the debate over violence and nonviolence and gave the battalions of nonviolent direct action their compelling historical moment," writes Tyson.

Promptly, King got on the bandwagon with a tour of southern college towns. In the previous year he had met with some followers of Gandhi in India and conducted a pilgrimage in his footsteps. This experience strengthened King's commitment to the gospel of nonviolent direct action.

On May 8-9 he came to Chapel Hill, where, already, sympathetic sit-ins had been under way. Lincoln High students had made their stand at the soda fountain at Colonial Drug Store on West Franklin. Before King's arrival, the student protest movement had shifted from boycotting to leafleting and was now organizing a sit-in campaign aimed at movie theaters.

What the protesters wanted was a local public accommodations ordinance. The resistance they faced can be read in this conclusion to an editorial in the Chapel Hill Weekly on March 31, 1960:

As unpopular as it might be, a man's prejudice is still a personal matter. If he chooses to indulge himself in it, then he alone must take the responsibility for it. Nobody has yet come up with a satisfactory reason why a community should assume the responsibility for him.

King spoke first in Northside to a crowd of about 400. As Kirk Ross recounted in a retrospective for the Chapel Hill News in 1998, he told the protesters,

"You are demonstrating a magnificent act--a magnificent act of non-cooperation with the forces of evil. You are not seeking to put stores that practice discrimination out of business. You are seeking to put justice in business."

Next, he spoke at Hill Hall on the UNC campus to a mixed audience.

"There must be no violence in the struggle for racial equality," he told the audience. "There is no longer a choice between violence and non-violence--there is only a choice between non-violence and non-existence."

The Rev. J.R. Manley of the First Baptist Church said, "It was like a new creation. He was able to energize people, and after he left it stayed around. It didn't die down for a very long time." Further, he said, "People were angry. There was a whole lot of hate, and I think he helped change that hate, helped to transform those bad energies to focus them into something positive."

Chapel Hill had become one of the focal points for the national civil rights movement. The nation's eyes were on Chapel Hill in those days, but as Joe Straley recalled, "we had to live here once [the national leaders] were gone." It was King's inspiration that sustained the movement locally long after he went on to the next town--and sustains it today.

Friday, November 05, 2004

Best bet on Bush's baffling bulge

Thursday, November 04, 2004

United States of the South

I wasn't expecting to come across this, a passage from W.J. Cash's The Mind of the South, published, after a long gestation, in 1941:

Proud, brave, honorable by its lights, courteous, personally generous, loyal, swift to act, often too swift, but signally effective, sometimes terrible in its action--such was the South at its best. And such at its best it remains today, despite the great falling away in some of its virtues. Violence, intolerance, aversion and suspicion toward new ideas, an incapacity for analysis, an inclination to act from feeling rather than from thought, an exaggerated individualism and a too narrow concept of social responsibility, attachment to fictions and false values, above all too great attachment to racial values and a tendency to justify cruelty and injustice in the name of those values, sentimentality and a lack of realism--these have been its characteristic vices in the past. And, despite changes for the better, they remain its characteristic vices today.

Cash killed himself, hung himself with his own necktie, in that same year, 1941. C. Vann Woodward was more optimistic about the future of the perpetually "New South," observes Jacob Levenson in the Columbia Journalism Review; he believed that somehow the legacy of Jim Crow could be overcome in a period of new economic growth, while a strong positive regional identity remained.

In the fullness of time, the South triumphed on the national political scene: "Governors like Jimmy Carter, William Winter, and Dale Bumpers encouraged biracial coalitions that cast an aura of reconciliation across the region." But the predicted demise of Jim Crow took a curious route. The shift from a historical allegiance to the Democrats, the party of white supremacy, to the Republicans, the party of Lincoln, took off when Goldwater denounced the Civil Rights Act. Lyndon Johnson, who succeeded in the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts, said that he knew he was giving the South to the Republicans "for a long time to come." Then, as Levenson reminds, Nixon aligned himself with Strom Thurmond.

But it was Reagan . . . who tightened the Republican hold on the region. Reagan’s success in the South can be viewed as an affirmation of both Cash’s and Woodward’s view of the region. Reagan skillfully employed a version of the cultural code that Cash had identified forty years earlier to overwhelmingly win the white southern vote. His first major campaign stop after gaining the 1980 nomination was near Philadelphia, Mississippi, the community in which the civil rights workers Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney were murdered. There he pledged to the almost all-white audience at the Neshoba County Fair—an obligatory stop on the Mississippi political circuit—that he believed in states’ rights. In another speech he denounced the welfare queen in designer jeans. At the same time, though, his message to southerners went beyond coded racial signals and incorporated a range of southern themes, some that had endured through two centuries, and others that spoke to Woodward’s transformed South. He solidified his connection to the evangelical right by speaking openly about his Christian faith, and at the same time offered tax cuts to appeal to the newly emergent middle-class, white, suburban southerner. In 1980 Reagan took every southern state except Georgia, and in 1984 he swept the region. The elder Bush did the same. And, of course, after Bill Clinton won some southern states in ’92 and ’96, George W. Bush swept the South in 2000, and is considered a good bet to do so again this year.

And the rest is our living history.

Wednesday, November 03, 2004

On not seeing red

I thought maybe we just didn't have the right kind of trees, until my neighbor said no, it's something about the weather this year. The maples should be red, but they're hanging on green and then abruptly turning to yellow and brown. Even the dogwoods are more brown than red.

Where is the red? There is a great sea of red, and North Carolina is in it, except that in Orange County, it is not much to be seen. We live in a bubble of blue.

From a true blue state comes some advice to Democrats on how to reconnect with the red states. This is the most-emailed article from today's Times.